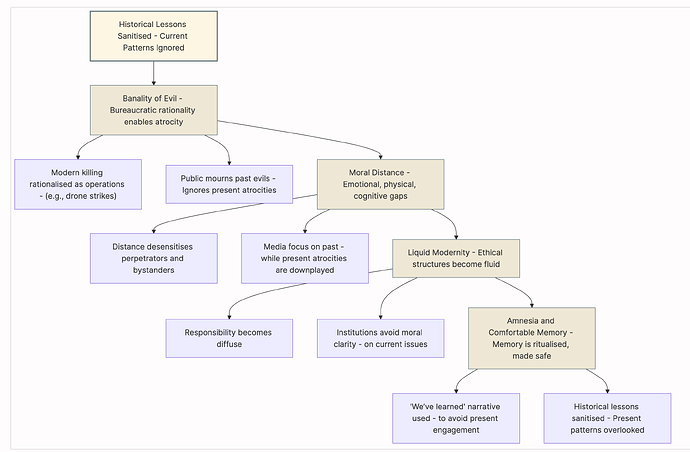

This has been inspired by Arendt, Bauman and Althusser to a degree.

I’m still struggling with the concept - but something seems to be there.

- Appearance of this bindspot or sense-making pattern

It’s partly to do with ritualising and domesticating memory to convert moral lessons into safe historical narratives. When we’re remembering the past in order to avoid engaging with the present - but not as in burying our heads in the sand - but as an active attempt to stop the enquiry.

- Psychological / sociological / ideological reasons behind it

There are multiple undercurrents going on - one is definitely trying to “conform” and share “vibes” - or do moral posturing, virtue signalling - but at the same time you don’t want to refer to anything that’s potentially controversial, so you stick so themes that are in the spirit of what you want to manifest and you know that others are equally likely to subscribe to them without touching on “dangerous” subjects

Its may be explained by the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence and assuming cognitive patterns that give us a functional but distorted image of the world and our place in it. There’s also an aspect of disavowal where people are often aware of contradictions or incoherence of their system - but continue participating because it’s safe - when people are knowingly fooled but act as if they are not.

Feel free to help out, if of interest. Maybe with building a better diagram or clarifying concepts.