Something I posted previously on Discussions.

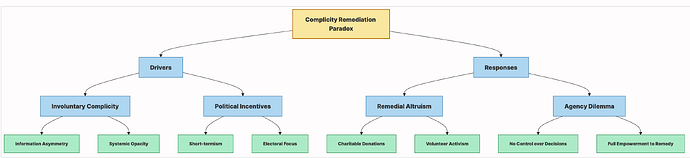

In the paradoxical constellation of modern paradigms and situations, there’s one hidden phenomenon that fascinates me. Until someone suggests a better term - I’ll call it Complicity Remediation paradox.

It’s a paradox that highlights the dual role played by us, the members of the society and the institutions that represent us - as both perpetrators and healers within a system that perpetuates certain harms.

The key aspects of the Complicity Remediation Paradox are:

- Involuntary Complicity - individuals unknowingly complicit in contributing to negative outcomes due to not being able to fully evaluate the impacts of the government’s decisions making or because the systemic structures are beyond immediate control. There is often a significant gap between the information available to policymakers and the general public. This asymmetry can lead to a lack of understanding among citizens about the full implications of government projects and policies.

- Political Incentives - Politicians are often incentivised to make decisions that will make them appear performant and boost their chances for re-election. This can lead to short-term thinking and a focus on visible, immediate results rather than long-term systemic change. The invisible gets hidden in the system that is sub-optimally transparent.

- Remedial Altruism - individuals willing to engage in altruistic actions to mitigate the negative impacts

- Systemic Dissonance and Feedback Delay - dissonance from living within systems that are misaligned with our personal values and the desire for social and environmental well-being. The consequences of harmful policies may take time to become apparent, and by the time they do, the damage may already be significant and the causal relationship obfuscated. This delay can make it challenging to address the root causes promptly.

- Agency Dilemma - dilemma regarding agency where it feels like people have very little control over the contributory aspects of the problems, but are fully empowered to participate in the remedial actions.

There is a stark contrast of “no control” over decisions but “full empowerment” when it comes to remedying them!

The Current Model

The current model often operates on a remedial approach, where the government undertakes or supports projects that, while economically beneficial in the short term, create negative externalities that charities and non-profits must then address. This creates a feedback loop that is both inefficient and ethically questionable.

The moral hazard in this scenario is that decision-makers in government may not be sufficiently incentivised to prioritise long-term social and environmental outcomes (or focus on the substance instead of appearance), as the immediate economic gains are more tangible and politically rewarding. This can lead to a misallocation of public funds, where the opportunity cost is the foregone benefits of investing in sustainable and just practices from the outset.

Democracy Angle

While not limited to democracies, the dynamics of this paradox may be more visible and pronounced in democratic societies due to the expectations of citizens of common good orientation and government accountability.

The link between the citizens and the government is established through our power to both elect the government and influence it through advocacy and public discourse. This paradox emerges when there’s a disconnect between the collective will of the people and the actions of our elected representatives and it’s defined by the opposing action, seemingly internally generated. Taxpayers might be unwilling participants behind government’s actions, but still fully legitimising them.

Examples

Wars and Military Conflicts

Complicity:

We, as taxpayers of democratic nations, pay taxes that are used to fund military operations. Some of these operations may result in civilian casualties, material damage, refugee crisis and destabilisation.

Remediation: The same citizens may donate to humanitarian organisation and charities that provide aid to affected war-torn regions to offset the damage caused by the conflict that their taxes helped finance.

Environmental Destruction:

Complicity: Consumers purchase goods and services that contribute environmental harm - deforestation, biodiversity loss, polluting industries.

Remediation: The same consumers invest their time and money to contribute organisations fight climate change or mitigate damage caused to the nature.

Social Injustice:

Complicity: Societal structures and institutions may be perpetuating systemic racism, various discrimination or other forms of social injustice. People participate in these systems through daily interactions, employment or consumption patterns.

Remediation: Citizens may volunteer their time or materially contribute to social justice organisations or initiatives. They can participate in advocacy campaigns to combat the very injustices that they are, through the taxation and representative leadership, standing behind.

In each of these example, the paradox lies in the fact that the same individuals or collectives, through their action or inaction, are contributing to systemic problems while at the same time trying to alleviate the consequences of those problems.

Externalising the Cost - Internalising the Benefits

Complicit Remediation paradox offers a good explanatino of how governments benefit from positive aspects of decisions and how they avoid or dilute their accountability and responsibility for the bad ones.

Externalising the Costs

When a government undertakes or supports activities that lead to negative outcomes without bearing the full cost of the remedial action - it’s externalising the costs. These costs are instead borne by the public, whether in the form of remedy costs, degraded environments, poor health or social injustice. So the government’s mistakes and negative impact get cushioned and hidden by the good effort of “non-governmental” collective of people, allowing the government to continue behaving recklessly and take risks that it wouldn’t otherwise.

Internalising the Benefits

At the same time, governments may internalise the benefits of such activities by taking credit for immediate positive impacts that came on the back of the negative aspects that remained hidden because of the offset of the cost externalisation. This shines a positive light on the elected representatives who are then encouraged to risk more and potentially further increase the effect of cost externalisation.

It’s difficult to evaluate what percentage of society engages in remedial actions and it probably differs significantly from one country to another. Still, it’s only a segment of a society that donates to charities, volunteers for social, environment or humanitarian causes, participates in related activism, makes lifestyle changes or supports businesses that engage in ethical practices.

This points at another injustice - that the contributing minority is also externalising the cost for the individuals that don’t make personal sacrifices in this accountability deficit re-balancing act.

Are Grassroots or Bottom-up Approaches to Systemic Change Perpetuating the Complicity-Remediation Paradox?

Grassroots and bottom-up approaches face challenges in affecting systemic changes due to the factors related to their relative capacity compared to top-down or direct system interventions.

They suffer from resource constraints and less access to powerful networks than the top-down efforts. Political influence that is required to make the right impact at the top is not readily available to often ideologically opposed activists.

Grassroots movements can be extremely fragmented and suffering from the narcissism of small differences. Their collective impact is reduced by not presenting a unified front needed to challenge the established systems.

While grassroots activists have knowledge about local issues, they may lack the broader perspective and expertise, which can make their efforts seem naive and lacking pragmatism.

All of these reasons make grassroots movements more likely to adopt a remedial focus such as cleaning up pollution or providing services to marginalised communities, rather than challenging the systems that create these issues.