Evolving Effective Altruism: from EA to Pragmatic Utopianism / Integral Altruism and a Second Renaissance

I am booting this as a meta-thread to pull together other threads and materials. Perhaps we can even create a mini-website ![]()

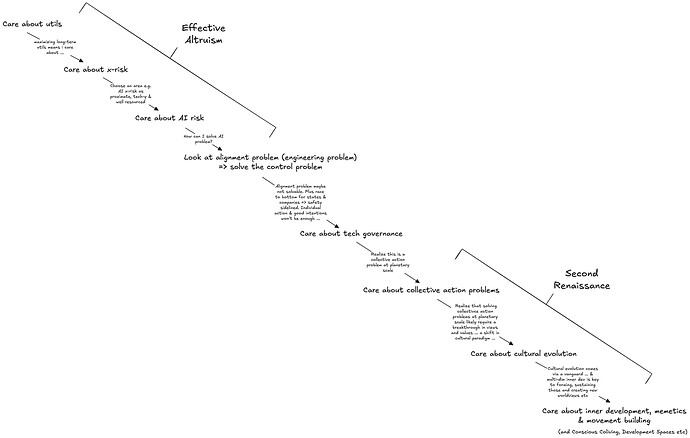

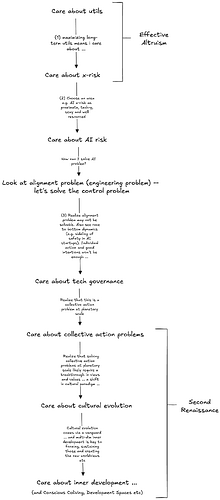

Fig 1: simplified illustrative evolution from Effective Altruism frame to Second Renaissance frame. (See below for vertical version of diagram)

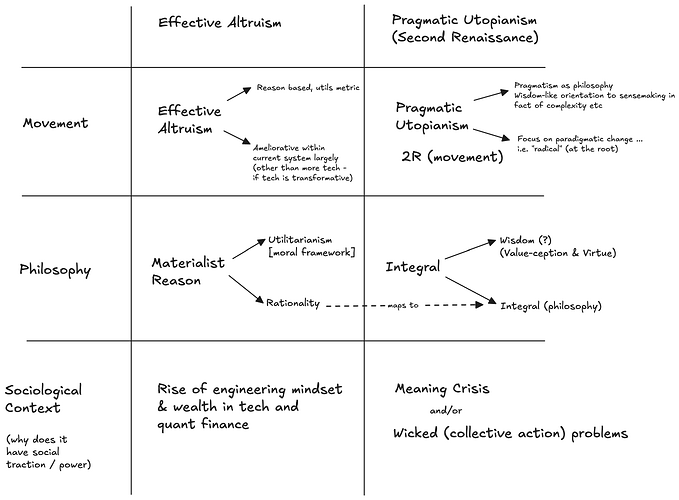

Fig 2: (imperfect) first draft of comparison of EA to PU/2R

Dialogs

Max + Rufus Dialogs on Evolving EA

By @MaxRamsahoye and @rufuspollock

Part I: Effective Altruism as philosophy and movement, its current status and historical evolution

We (Rufus Pollock and Max Ramsahoye) discuss the evolution of Effective Altruism (EA) from a philosophy to a movement, emphasizing its focus on using reason and evidence to maximize welfare.

We highlight EA’s historical roots in global poverty alleviation, economic growth, and existential risks, particularly AI. The conversation also touches on the shift towards AI safety and governance, with organizations like 80,000 Hours and Open Philanthropy focusing increasingly on AI risks.

We discuss the challenges of AI safety, emphasizing the failure of current approaches to ensure alignment without significant slowdowns.

We discuss critiques of Effective Altruism, citing the “drunkard and the lamppost problem” and the difficulty of determining the importance of AI risk over other global issues. We also discuss the implementation problems and the need for global coordination. We discuss the concept of coordination problems and a “Moloch trap,” where competitive pressures drive rapid AI development despite safety concerns.

We conclude by suggesting a need for cultural evolution and an evolution of effective altruism towards pragmatic utopianism, with an emphasis on wisdom and collective action beyond narrow rationalism.

Part II: Challenges and critiques of Effective Altruism and potential shift towards Pragmatic Utopianism

Rufus Pollock and Max Ramsahoye discuss some of the challenges and critiques of Effective Altruism (EA) and how it could evolve towards pragmatic utopianism.

Rufus Pollock and Max discuss the evolution of Effective Altruism (EA), highlighting its strengths and challenges. They critique the focus on techno-solutionism and capitalist realism, emphasizing the need for systems change.

They argue that EA’s emphasis on measurable impacts often overlooks broader, less quantifiable issues like collective action problems and cultural alignment.

They propose a shift from rationality to wisdom, advocating for a pragmatic utopianism that combines incremental change with radical vision for paradigmatic evolution. They stress the importance of addressing value misalignment and principal-agent problems, and call for a cultural evolution to solve collective action issues and ensure long-term sustainability.

They discuss the need for a comprehensive approach to Effective Altruism (EA) that integrates human psychology, wisdom traditions, and inner sciences like cognitive science and neuroscience.

They suggest that the future of science will involve both outer (ecological and system sciences) and inner (cognitive and neuroscience) disciplines. Finally, they highlight the wisdom gap between technological and psychological/social disciplines, referencing Comte’s hierarchy of sciences and the potential for a mature science of the mind and society to manage our technological powers.

Jonah & Rufus “Evolving Effective Altruism” dialog with a focus on wisdom

By @JonahW + @rufuspollock

Sub-threads

- A path from Effective Altruism to Second Renaissance (Pragmatic Utopianism)

- Connection, learnings, analogies and differences with Effective Altruism (EA) for Second Renaissance etc

- From Effective Altruism to Pragmatic Utopianism & Second Renaissance (aka integral/wise altruism)

Other relevant materials

- Reflections on Effective Altruism · Rufus Pollock Online - old points from 2017

- Pragmatic Utopianism

- Wisdom Gap

- https://metacrisis.info/

- https://www.integralaltruism.com/

From Effective Altruism to Pragmatic Utopianism: Evolving the Ethos of Doing Good

Outline by Rufus (all errors are mine)

Effective Altruism (EA) is one of the most influential philosophical and practical movements in the contemporary landscape of ethics and action. Born at the intersection of utilitarian ethics, rationalist epistemology, and Silicon Valley engineering culture, EA seeks to maximize the positive impact of one’s resources—especially money, talent, and attention—through rigorous cost-benefit analysis and prioritization. Its proponents emphasize doing “the most good,” often understood as saving or improving the largest number of lives for the lowest cost.

However, as the global landscape veers further into what scholars call the polycrisis—interlocking environmental, technological, social, and political crises—it is increasingly clear that EA, in its current form, may be necessary but not sufficient. It risks becoming a narrow framework, blind to the very cultural and ontological transformations required to address the deeper systemic roots of our predicament. What is needed is not an abandonment of EA’s virtues—its clarity, ambition, and moral seriousness—but an expansion into a new integrative paradigm: a pragmatic utopianism aligned with a Second Renaissance.

At its core, EA embodies several powerful assumptions. It places a strong emphasis on tractability, measurability, and marginal impact. The use of quantitative reasoning—epitomized in figures such as “$5,000 to save a life”—enables clear communication and accountability. Yet this same methodology narrows the range of “admissible” moral actions. Causes that are not easily measurable (like cultural renewal, governance reform, or inner development) are frequently sidelined.

This leads to one of the most profound limitations of EA: a form of epistemic tunnel vision. EA tends to prioritize domains that resemble engineering problems—AI safety, biosecurity, malaria nets—while de-emphasizing areas where systems are nonlinear, culturally embedded, and irreducibly complex. For instance, while existential risk from AI is taken seriously, governance-based approaches are often dismissed as “hopeless,” a view explicitly stated in Bostrom’s early work. The result is a self-fulfilling loop where collective action is seen as infeasible, and therefore never seriously attempted.

Compounding this, EA has traditionally been skeptical of spiritual traditions, mystical claims, and subjective or phenomenological accounts of well-being. Concepts such as liberation in the Buddhist sense—or flourishing as defined by inner transformation—are foreign to the analytic, externalist frameworks dominant in EA. Consequently, entire dimensions of human experience are excluded from its calculus.

The challenge, then, is not only philosophical but cultural. EA arises within a broader late-modern worldview: one that valorizes individualism, techno-solutionism, and quantification. Its neglect of cultural evolution—both as a field of inquiry and as a strategic frontier—is not incidental but systemic. Where governance and culture are acknowledged, they are typically treated as exogenous constraints or background conditions, not primary sites of transformation.

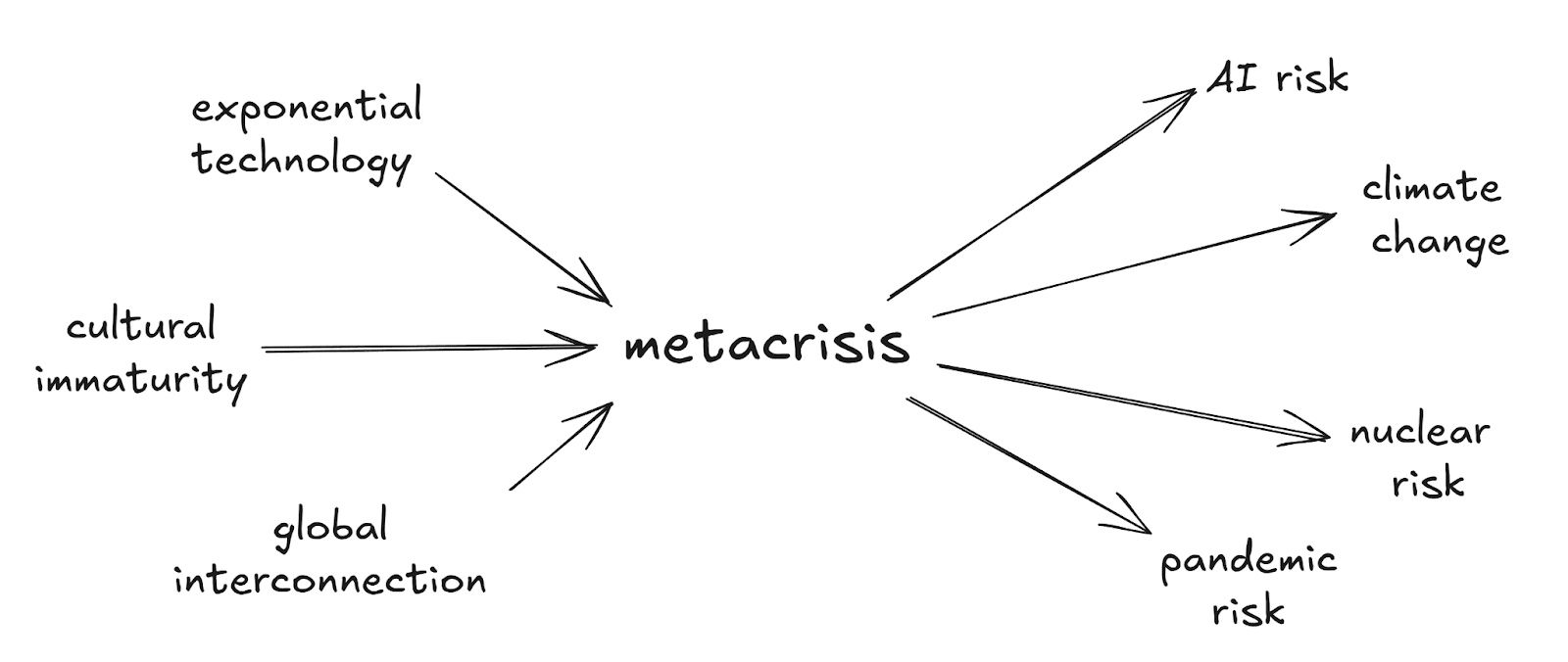

To evolve beyond these limits, we must imagine a path from EA to something broader: a pragmatic utopianism. This path involves recognizing the irreducibility of systems problems, the indispensability of cultural narratives, and the centrality of inner development. It means understanding the metacrisis not just as a collection of urgent risks, but as a civilizational transition requiring new ways of knowing, being, and relating.

Pragmatic utopianism does not reject rigor or strategic thinking. Rather, it insists that our metrics of success must include cultural resonance, institutional durability, and psycho-spiritual flourishing. It affirms the role of mysticism, art, and inner work not as luxuries but as generative engines of civilizational renewal. And it calls for courage: the courage to act beyond the measurable, to invest in the invisible, and to believe that long-term, systemic, and cultural interventions are not only necessary—but effective.

This does not mean abandoning EA. It means transcending it. The transition from EA to Pragmatic Utopianism and a Second Renaissance is not a repudiation, but a maturation—a movement from adolescence to adulthood in our ethical imagination. It means embracing complexity, cultivating wisdom, and holding space for the unknown.

As our crises deepen, the time for this transition is now.